OREGON—(ENEWSPF)—July 24, 2013. Editor’s Note: We wish to thank our colleagues at the Drug Policy Alliance for providing these two powerful and thought-provoking pieces: one by Drug Policy Alliance Communications Director, Sharda Sekaran, and the second by best-selling author, Michelle Alexander.

Huffington Post

In Order to Address Racism, We Must Confront the Drug War, Sharda Sekaran, July 24, 2013

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sharda-sekaran/drug-war-racism_b_3639579.html

This past week has brought an intense time of reflection and critical self-examination for many Americans. In the wake of the George Zimmerman verdict, there have been emotionally-charged conversations about the way young black men are viewed in the U.S. and how valued their lives are. All the way up to President Obama we are witnessing soul-searching attempts to confront the complicated role of race in our culture. In a public address, President Obama said 35 years ago, he could have been Trayvon Martin and was routinely racially profiled before he became a senator.

Revealed throughout the Zimmerman trial, as Trayvon Martin’s character was scrutinized for signs of how threatened Zimmerman may have felt by him, was the uncomfortable truth that racism results in black men being commonly viewed as menacing simply for being human.

From clothing to intoxicants, what is normal and innocuous in another context becomes sinister when associated with black men and boys. Mark Zuckerberg’s hoodie is a sign of millennial individuality and irreverence, whereas Trayvon’s hoodie is a sign of being a “wannabe gangster.” From Martha Stewart to Justin Bieber, marijuana is becoming increasingly socially acceptable. And although no one recommends marijuana use by teenagers, when was the last time someone made a case for justifiable homicide of a suburban white kid by noting trace amounts of THC found in their system, as was done in the case of Trayvon?

Being black means living a life saturated by double standards. When the skin you live in is viewed as inherently suspicious, anything you do can provoke fear and hostility. It takes a special effort to convince people of the humanity and worth of a young black man in a way that is not required for others. The day after the Zimmerman verdict, a friend and I went to see the film “Fruitvale Station,” a poignant and powerful account of the life of Oscar Grant, a young black man from Oakland, and the events leading up to his death at the hands of a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) officer in 2009.

Trayvon and Oscar were from opposite sides of the country and in many ways lived different lives but in the aftermath of their murders, as arguments were put forth for why they could have been seen as suspicious or potentially threatening, a history of involvement with drugs was cited. Drugs remain an enduring part the collection of social and historical biases commonly summoned to put the character of young black men under a microscope. The underlying assumption seems to be it is not so much a matter what you do but who you are.

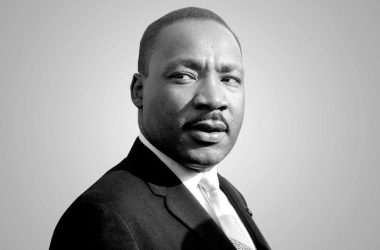

From caffeine to nicotine to aspirin to alcohol, when was the last time most of us have experienced a truly “drug free” day in our lives? By and large, we regularly consume some sort of substance that alters how we feel or offers pleasure instead of pain. This is why drug prohibition has been such a pernicious tool for perpetuating bias, corruption and bigotry. When the power is granted to selectively criminalize behavior that everyone engages in, unequal applications of law and social judgment are inevitable. This is why civil rights advocate and academic Michelle Alexander calls the drug war “The New Jim Crow.”

Frank conversations about race at the national level are long overdue. If any good is come from the Trayvon Martin tragedy, hopefully it will include bringing this dialogue to the forefront. But we absolutely cannot talk about race without talking about the war on drugs. This failed social experiment not only leads to the disproportionate targeting, arrest, conviction and incarceration of people of color, despite equal rates of drug consumption across race, it fuels the underlying thread of judgment, stigma and marginalization that permeates how we value human life and enable acts of violence.

Sharda Sekaran is managing director of communications for the Drug Policy Alliance (www.drugpolicy.org)

This piece first appeared on the Drug Policy Alliance blog.

Time Magazine

The Zimmerman Mind-Set, By Michelle Alexander, July 29, 2013

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2147697,00.html

Back in 1903, in his groundbreaking book The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois argued that the defining element of African-American life was being viewed as a perpetual problem–one’s very existence as a problem to be dealt with, managed and controlled but never solved. More than 100 years later, DuBois’ rhetorical question seems as relevant as ever: How does it feel to be a problem?

There is a profound difference, of course, between having problems–which all people are allowed–and being a problem. One of the reasons that Trayvon Martin’s tragic death resonated so powerfully with millions of people of color, black and brown men in particular, is that it was one of those rare situations in this so-called era of colorblindness when suddenly the curtain was pulled back. All the usual rationalizations for routinely treating young black men as problems and up to no good, were stripped away. There was just a young teenager on the phone with a girl, carrying a bag of Skittles and an iced tea, and he was viewed for no logical reason as scary, out of place, on drugs–someone who needs to be confronted, interrogated and put in place.

Our criminal-justice system has for decades been infected with a mind-set that views black boys and men in particular as a problem to be dealt with, managed and controlled. This mind-set has fueled a brutal war on drugs, a get-tough movement and a prison-building boom unprecedented in world history.

Today, millions of people of color are stopped, interrogated and frisked as they are walking to school, driving to church or heading home from the store. In 2011 alone, the New York City police department stopped and frisked more than 600,000 people. The overwhelming majority were black and brown men who were innocent of any crime or infraction. Their mere existence was cause for concern, just as the sight of Trayvon Martin walking leisurely through his own neighborhood was enough to make George Zimmerman call the police.

Studies have consistently shown that people of color are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than whites, yet black people have been arrested and incarcerated at grossly disproportionate rates during the 40-year-old war on drugs. If people who abuse illegal drugs were viewed as people who have real problems–rather than people who are problems–then drug treatment would be the obvious and rational response rather than putting people struggling with addiction in cages, treating them like animals and stamping them with a lifelong badge of inferiority.

Once released from prison, most people find that their punishment is far from over. Felons are typically stripped of the very rights supposedly won in the civil rights movement, including the right to vote, the right to serve on juries and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to education and public benefits. They’re relegated to a permanent undercaste. Unable to find work or housing, most wind up back in prison within a few years. Black men with criminal records are the most severely disadvantaged group in the labor market. In some places, more than 50% of people are in this demographic.

Research shows that racial disparities in violent crime disappear when you control for joblessness. Unemployed men of all races are equally likely to be violent, particularly if they are chronically without work. But rather than viewing high levels of violent crime in ghettoized communities as a symptom of the deeper economic and social ills, black men and boys are viewed as the problem itself and treated accordingly. Jobs are promised but almost never delivered, and schools are allowed to fail as ever bigger prisons are built to manage “the problem.”

Trayvon Martin will not be the last black boy who dies or goes to jail or gives up on his life because he was viewed and treated as nothing but a problem. We are all guilty of being too quiet for too long. Let it be said hereafter that we were quiet no more.

Alexander, a civil rights lawyer, is the author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

Source: www.drugpolicy.org